BBCに水産資源管理の記事が掲載された。なかなか面白い記事なので、要約をしてみた。

Collective rights ‘offer hope for global fisheries’

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-24209950

アイスランドのアーナソン教授の見解。(Prof Arnason outlined his views at the ICES science conference in Iceland.)

世界の水産資源は乱獲と、生態系の破壊という深刻な問題を抱えている。

一部の海域では、水産資源の減少が停止したようである(オセアニアや北米の資源管理をしている国のことを指す)

世界中の最も貴重な水産資源は壊滅的な状況だが、良いニュースもある。乱獲問題を解決する方法がすでに発見されているのだ。

その方法とは、個人の漁獲権利を保障するような枠組みの漁業管理を導入することで、操業者が、長期的な視点から、漁業の持続性や資源回復に関心を抱くようにすることだ。。

“We have a severe problem of over-exploitation of global fish stocks, with the associated damage of marine ecosystems,” he told BBC News ahead of his presentation.

“There is some indication that things may have stopped declining – at least in some parts of the world.

“However, we have essentially devastated the world’s most valuable fish stocks but the good news is that we basically know how to solve the problem.

“That is by installing fisheries management regimes based on individual rights to fisheries or fishing communities so that operators, on behalf of the population, will find it in their own interests to treat the fisheries carefully and sustain or even rebuild them with long-term benefits to them and others.”

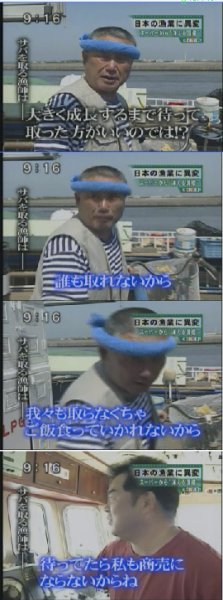

漁場に行って、捕れる魚を捕らなければ、他の人間が漁獲してしまう状況では、乱獲をしなかった漁業者は、結果として、さらに多くを失うことになる。漁業者間の協調関係がなければ、乱獲をせざるを得ない状況に追い込まれる。そうすることが良くないことだと解っていたとしても。これが、共有地の悲劇である。

“If you are only one of many and you cannot co-ordinate your actions with others then you are almost forced to overexploit, even if it is against your better knowledge.

“But if you do not go out and take what you can then others will and you will lose even more – this is the tragedy of the commons,” said Prof Arnason,

機能することが経験的に知られている唯一の方法は、個人の所有権を認めることです。

“The only system that empirically has been found to function have been based on private property rights,” he recalled.

一般的に行われているのは、漁場の利用権を漁業者グループに与えることです。これは地域漁業権と呼ばれています。こういう方法は貝のような定住性の資源を管理する場合に有効です。

“In fisheries, this is usually done by saying that an area of the ocean belongs to a group – this is called territorial rights. It works pretty well if you have sedentary species, such as shellfish.

移動性の資源では定量的に漁獲する権利を与えるのが一般的です。全体の漁獲枠を定めた上で、たとえばその1%と言った具合に、決まった割合を個人に配分します。

“When you are dealing with fish stocks that are moving about then you usually have quantitative catch rights. So out of the total allowable catch for that particular stock, you would get a fixed [allocation], for example 1%.

そうすれば仲間の漁業者と競争をしないで済むのです。その権利が長期的なものであれば、漁業者は水産資源の持続性に関心を払うようになります。水産資源/生態系が良い状態に保たれることによって、自分に配分される漁獲枠が増えるからです。

“You then do not have to race or compete against your fellow fishermen. If this right is a long-term right, you also have a greater interest in the welfare of the fish stock and ecosystem because the amount you are allowed to catch increases as the state of the fish stocks/ecosystem improves.

会社の株主が、会社の成功を望むような感じになるのです。

“So you become a little bit like a shareholder in a company, you want the company to succeed.”

こういった管理を行うには、強制力と監視が必要になります。そのための費用は先進国では大した負担にはなりません(水揚げ金額の3%ぐらいです)。しかし、何千もの小規模でローテクな漁船がひしめいている途上国では、管理コストが問題になります。

But he explained that these measures have to be enforced and monitored.

While, he argued, this was not prohibitively expensive in fleets of industrialised nations (about 3% of the value of the landed catch), it became problematic in many developing nations, where fisheries were made up from thousands of small-scale low-tech fishing vessels.

管理費用がまかなえない途上国では、漁業者のコミュニティーに漁業権を与える方式が良いだろう。

その場合には、すでに減少した資源をどのように回復するかという難しい問題がある。

世界の漁業はこちらの方向に向かっているので、私はその未来については楽観している。

総評

「小規模定住性資源は地域漁業権で、遊泳性資源は個別漁獲枠方式で」という彼の主張は、世界の水産資源研究者の間では常識になっている。本当に当たり前の話なんだけど、その当たり前の話が理解できている研究者が日本にはほとんどいない。日本では、細かく区切った漁場の排他的利用権を地元の漁協に与えている。この方式で管理しうるのは小規模定住性の資源だけ。この場合、移動性の魚は、「誰かに獲られる前に獲っておけ」と言うことになる。日本では、サバもクロマグロも商業価値が出るまえの未成魚の段階でほとんど漁獲されてしまう。なぜそういうもったいない捕り方をするかというと、「自分が獲らなくても他の誰かが獲ってしまうから」だ。日本の漁業は、この記事で批判されているような「仲間との競争で乱獲をせざるを得ない状況」にあるのだ。

遊泳性の資源は国が全体の漁獲量の調整をしたうえで、早獲り競争にならないように、漁獲枠を個別配分しなければならない。そうしなければ、魚の奪い合いになってしまう。「早獲り競争を放置していたら漁業が非生産的になる」というのは水産資源学の常識なのだが、日本の水産業はまさにその状態にある。構造的な問題を放置したまま、場当たり的に補助金を配って、問題をごまかしてきた。

ノルウェーでは、この記事で書かれているように、全体の漁獲枠を定めた上で、個々の漁業者に漁獲枠を個別配分をしている。漁業者は、自分の取り分が確保されているので、ライバルよりも早く魚を捕る必要が無い。だから、一番良い時期に、一番価値が高いサイズのサバを捕るように努力をする。日本で獲っているような未成熟な小型のサバの群れは、注意深く避けて操業する。結果として、日本ではサバが安定供給できないが、ノルウェーでは良質のサバが安定供給できる。日本のサバの加工品は、押し寿司にせよ、へしこにせよ、ほとんどがノルウェー産だ。この違いは、日本とノルウェーの漁業者のモラルの問題では無い。この状況を招いたのは、遊泳性の資源を適切に利用する上で必要な漁獲規制が日本には無いからである。日本の漁獲制度の欠陥の問題なのだ。

日本がやるべきことは決まっている。アジ・サバ・イワシ・クロマグロなど遊泳性の資源に個別漁獲枠制度を導入することである。この記事にも書かれているように、この方法が大規模資源の乱獲を解消する特効薬なのだ。

- Newer: 宮城県復興特区における漁民の自治の侵害について

- Older: TPPが日本の水産業に与える影響について

Comments:1

- ああ 13-12-03 (火) 11:13

-

個人の取り分を決めてしまうのは確かにコモンズの悲劇を解消するかもしれません。

しかし、すでに大半の漁業主の認識はそうですが、

水産資源がより漁業主の固有の資産かのように捉えられるのではないでしょうか。漁業への新規参入が阻害されるだけではなく、

レクリエーションとしてのスキューバダイビングであったり、釣りであったりも制限される可能性に懸念を抱きます。

Trackbacks:0

- Trackback URL for this entry

- http://katukawa.com/wp-trackback.php?p=5309

- Listed below are links to weblogs that reference

- 水産業における世界の常識と日本の非常識 from 勝川俊雄公式サイト